Situated in California’s iconic and gorgeous Eastern Sierra, Mammoth Lakes is a breathtaking mountain town in Mono County, surrounded by the Inyo National Forest. With a population of just over 7,000 people, this charming destination is a year-round haven for outdoor enthusiasts. Renowned for its world-class skiing and snowboarding at Mammoth Mountain, it also offers hiking, fishing, and biking trails that draw adventurers seeking stunning alpine vistas and urban escapes. Just 100 miles from the Yosemite Valley floor, Mammoth captivates visitors with its rugged beauty and vibrant community spirit, making it a beloved base for exploring the Sierra Nevada, or a favorite California glamping destination.

Yet, so far in 2025, Mono County health officials have confirmed a third hantavirus-related death in Mammoth Lakes, raising alarm bells in this idyllic getaway town. The latest victim, a young adult, succumbed to the virus in early April, following two other fatalities in February and March. Dr. Tom Boo, Mono County’s public health officer, described the losses as “tragic and alarming,” noting that the source of the most recent infection remains unclear, with no evidence of rodent activity (which is how hantavirus is spread) in the victim’s home and only minimal signs at their workplace (via Mono County). Typically, cases of the hantavirus peak in late spring or summer, making these early-season deaths unusually concerning. With no preventative vaccine available, understanding hantavirus and taking precautions is critical for residents and visitors alike to stay safe in this popular outdoor destination.

Understanding Hantavirus: A rare but deadly threat

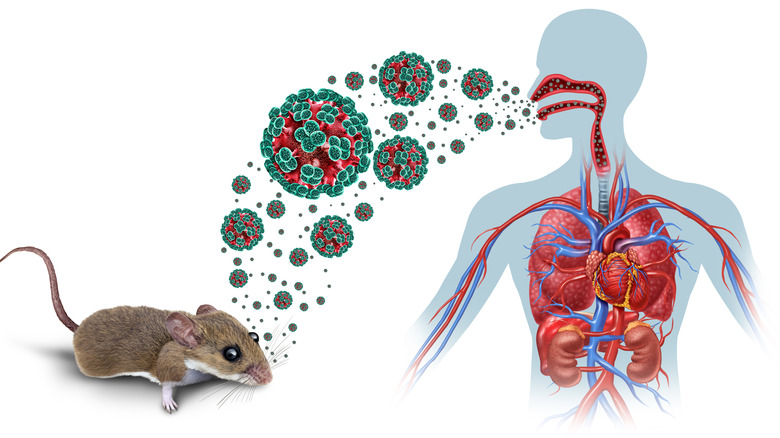

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, hantavirus is a severe, sometimes fatal respiratory illness caused by viruses carried primarily by rodents, with deer mice being the main culprit in North America. In Mammoth Lakes, deer mice are widespread, and their droppings, urine, or saliva can transmit the virus to humans. Infection typically occurs by inhaling contaminated particles, touching infected materials and then the face, or, rarely, through bites or contaminated food. The virus does not spread person to person, but its rarity – fewer than 900 cases reported in the United States since 1993 – belies its danger, with a mortality rate of about 38%.

Symptoms emerge one to eight weeks after exposure, beginning with flu-like symptoms: fever, fatigue, muscle aches, headaches, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or abdominal pain. Unlike other common respiratory illnesses, early hantavirus rarely causes a runny nose or sore throat. Within four to ten days, some patients recover, but others develop Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome (HPS), which is marked by coughing and severe shortness of breath. HPS can escalate rapidly, potentially leading to respiratory failure within days. Immediate medical attention is needed if breathing difficulties arise after exposure to mice or rodents. Activities like cleaning enclosed spaces infested with rodents, such as sheds, cabins, vehicles, or campers, or disturbing rodent waste heighten the risk, particularly in poorly ventilated areas where contaminated dust can become airborne.